How Was the Dada Art Movement Described as Being Similar to New Media Activism

Francis Picabia: left, Le saint des saints c'est de moi qu'il s'agit dans ce portrait, 1 July 1915; middle, Portrait d'une jeune fille americaine dans fifty'état de nudité, 5 July 1915; correct, J'ai vu et c'est de toi qu'il s'agit, De Zayas! De Zayas! Je suis venu sur les rivages du Pont-Euxin, New York, 1915

Dada artists, group photograph, 1920, Paris. From left to correct, Dorsum row: Louis Aragon, Theodore Fraenkel, Paul Eluard, Clément Pansaers, Emmanuel Fay (cut off).

Second row: Paul Dermée, Philippe Soupault, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes.

Front row: Tristan Tzara (with monocle), Celine Arnauld, Francis Picabia, André Breton.

Comprehend of the first edition of the publication Dada, Tristan Tzara; Zürich, 1917

Dada () or Dadaism was an art motility of the European advanced in the early 20th century, with early centres in Zürich, Switzerland, at the Cabaret Voltaire (c. 1916). New York Dada began c. 1915,[ii] [3] and after 1920 Dada flourished in Paris. Dadaist activities lasted until the mid 1920s.

Developed in reaction to World War I, the Dada move consisted of artists who rejected the logic, reason, and aestheticism of modern capitalist society, instead expressing nonsense, irrationality, and anti-bourgeois protest in their works.[4] [five] [6] The fine art of the movement spanned visual, literary, and sound media, including collage, sound verse, cut-upwardly writing, and sculpture. Dadaist artists expressed their discontent toward violence, state of war, and nationalism, and maintained political affinities with radical left-fly and far-left politics.[7] [8] [9] [10]

There is no consensus on the origin of the motility'south name; a mutual story is that the German language artist Richard Huelsenbeck slid a newspaper knife (letter-opener) at random into a dictionary, where it landed on "dada", a colloquial French term for a hobby horse. Jean Arp wrote that Tristan Tzara invented the word at 6 p.m. on half dozen February 1916, in the Café de la Terrasse in Zürich.[11] Others note that it suggests the first words of a child, evoking a childishness and absurdity that appealed to the group. All the same others speculate that the word might have been called to evoke a similar meaning (or no meaning at all) in any language, reflecting the motility'south internationalism.[12]

The roots of Dada prevarication in pre-war avant-garde. The term anti-art, a precursor to Dada, was coined by Marcel Duchamp around 1913 to characterize works that challenge accepted definitions of art.[xiii] Cubism and the evolution of collage and abstract art would inform the motion's disengagement from the constraints of reality and convention. The work of French poets, Italian Futurists and the German language Expressionists would influence Dada'south rejection of the tight correlation between words and significant.[14] Works such as Ubu Roi (1896) by Alfred Jarry and the ballet Parade (1916–17) by Erik Satie would also be characterized as proto-Dadaist works.[xv] The Dada movement'south principles were get-go collected in Hugo Ball'southward Dada Manifesto in 1916.

The Dadaist motion included public gatherings, demonstrations, and publication of art/literary journals; passionate coverage of art, politics, and civilisation were topics often discussed in a variety of media. Primal figures in the movement included Jean Arp, Johannes Baader, Hugo Brawl, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, George Grosz, Raoul Hausmann, John Heartfield, Emmy Hennings, Hannah Höch, Richard Huelsenbeck, Francis Picabia, Man Ray, Hans Richter, Kurt Schwitters, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Tristan Tzara, and Beatrice Wood, among others. The movement influenced afterwards styles like the avant-garde and downtown music movements, and groups including Surrealism, nouveau réalisme, popular art and Fluxus.[ not verified in body ]

Overview [edit]

Francis Picabia, Dame! Illustration for the encompass of the journal Dadaphone, n. 7, Paris, March 1920

Dada was an informal international movement, with participants in Europe and Due north America. The beginnings of Dada correspond with the outbreak of World War I. For many participants, the motion was a protest against the conservative nationalist and colonialist interests, which many Dadaists believed were the root crusade of the state of war, and confronting the cultural and intellectual conformity—in art and more than broadly in society—that corresponded to the war.[16]

Avant-garde circles outside French republic knew of pre-war Parisian developments. They had seen (or participated in) Cubist exhibitions held at Galeries Dalmau, Barcelona (1912), Galerie Der Sturm in Berlin (1912), the Armory Bear witness in New York (1913), SVU Mánes in Prague (1914), several Jack of Diamonds exhibitions in Moscow and at Moderne Kunstkring, Amsterdam (between 1911 and 1915). Futurism developed in response to the work of various artists. Dada afterwards combined these approaches.[14] [17]

Many Dadaists believed that the 'reason' and 'logic' of bourgeois capitalist gild had led people into war. They expressed their rejection of that ideology in creative expression that appeared to decline logic and embrace chaos and irrationality.[5] [6] For example, George Grosz after recalled that his Dadaist fine art was intended as a protest "against this world of mutual destruction".[five]

Co-ordinate to Hans Richter Dada was not art: it was "anti-art."[16] Dada represented the reverse of everything which fine art stood for. Where fine art was concerned with traditional aesthetics, Dada ignored aesthetics. If art was to appeal to sensibilities, Dada was intended to offend.

Additionally, Dada attempted to reflect onto human perception and the chaotic nature of gild. Tristan Tzara proclaimed, "Everything is Dada, as well. Beware of Dada. Anti-dadaism is a disease: selfkleptomania, man's normal condition, is Dada. Only the real Dadas are against Dada".[eighteen]

As Hugo Ball expressed it, "For us, art is non an end in itself ... but information technology is an opportunity for the true perception and criticism of the times nosotros live in."[19]

A reviewer from the American Art News stated at the time that "Dada philosophy is the sickest, well-nigh paralyzing and most subversive thing that has ever originated from the brain of human." Fine art historians accept described Dada as being, in large part, a "reaction to what many of these artists saw equally zippo more than an insane spectacle of commonage homicide".[twenty]

Years later, Dada artists described the move as "a phenomenon bursting forth in the midst of the postwar economic and moral crisis, a savior, a monster, which would lay waste to everything in its path... [It was] a systematic work of destruction and demoralization... In the finish it became aught but an act of sacrilege."[20]

To quote Dona Budd's The Language of Art Noesis,

Dada was born out of negative reaction to the horrors of the First World War. This international move was begun by a group of artists and poets associated with the Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich. Dada rejected reason and logic, prizing nonsense, irrationality and intuition. The origin of the proper name Dada is unclear; some believe that it is a nonsensical give-and-take. Others maintain that information technology originates from the Romanaian artists Tristan Tzara's and Marcel Janco'south frequent use of the words "da, da," significant "yes, yeah" in the Romanaian language. Another theory says that the name "Dada" came during a meeting of the grouping when a paper pocketknife stuck into a French–German dictionary happened to betoken to 'dada', a French word for 'hobbyhorse'.[half dozen]

The movement primarily involved visual arts, literature, verse, art manifestos, art theory, theatre, and graphic pattern, and concentrated its anti-state of war politics through a rejection of the prevailing standards in art through anti-art cultural works.

The creations of Duchamp, Picabia, Human Ray, and others between 1915 and 1917 eluded the term Dada at the fourth dimension, and "New York Dada" came to be seen every bit a post facto invention of Duchamp. At the outset of the 1920s the term Dada flourished in Europe with the help of Duchamp and Picabia, who had both returned from New York. Notwithstanding, Dadaists such every bit Tzara and Richter claimed European precedence. Art historian David Hopkins notes:

Ironically, though, Duchamp's late activities in New York, along with the machinations of Picabia, re-bandage Dada's history. Dada's European chroniclers—primarily Richter, Tzara, and Huelsenbeck—would eventually become preoccupied with establishing the pre-eminence of Zurich and Berlin at the foundations of Dada, but it proved to be Duchamp who was well-nigh strategically brilliant in manipulating the genealogy of this advanced formation, deftly turning New York Dada from a late-comer into an originating force.[21]

History [edit]

Dada emerged from a period of creative and literary movements like Futurism, Cubism and Expressionism; centered mainly in Italy, France and Germany respectively, in those years. Still, unlike the earlier movements Dada was able to establish a broad base of support, giving ascension to a motility that was international in scope. Its adherents were based in cities all over the world including New York, Zürich, Berlin, Paris and others. At that place were regional differences like an accent on literature in Zürich and political protest in Berlin.[22]

Prominent Dadaists published manifestos, just the movement was loosely organized and at that place was no central hierarchy. On fourteen July 1916, Ball originated the seminal manifesto. Tzara wrote a 2d Dada manifesto,[23] [24] considered of import Dada reading, which was published in 1918.[25] Tzara'due south manifesto articulated the concept of "Dadaist cloy"—the contradiction implicit in avant-garde works betwixt the criticism and affidavit of modernist reality. In the Dadaist perspective modern art and culture are considered a blazon of fetishization where the objects of consumption (including organized systems of idea like philosophy and morality) are chosen, much similar a preference for cake or cherries, to fill up a void.[26]

The shock and scandal the motion inflamed was deliberate; Dadist magazines were banned and their exhibits closed. Some of the artists even faced imprisonment. These provocations were part of the amusement simply, over time, audiences' expectations eventually outpaced the movement'due south capacity to deliver. Equally the artists' well-known "sarcastic express joy" started to come from the audience, the provocations of Dadaists began to lose their bear on. Dada was an active motion during years of political turmoil from 1916 when European countries were actively engaged in World War I, the conclusion of which, in 1918, ready the stage for a new political social club.[27]

Zürich [edit]

There is some disagreement nigh where Dada originated. The motility is commonly accepted by well-nigh art historians and those who lived during this period to have identified with the Cabaret Voltaire (housed inside the Holländische Meierei bar in Zürich) co-founded by poet and cabaret vocalizer Emmy Hennings and Hugo Brawl.[28] Some sources propose a Romanaian origin, arguing that Dada was an adjunct of a vibrant artistic tradition that transposed to Switzerland when a grouping of Jewish modernist artists, including Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco, and Arthur Segal settled in Zürich. Before Globe War I, similar art had already existed in Bucharest and other Eastern European cities; information technology is likely that Dada's goad was the inflow in Zürich of artists like Tzara and Janco.[29]

The name Cabaret Voltaire was a reference to the French philosopher Voltaire, whose novel Candide mocked the religious and philosophical dogmas of the solar day. Opening night was attended past Brawl, Tzara, Jean Arp, and Janco. These artists along with others like Sophie Taeuber, Richard Huelsenbeck and Hans Richter started putting on performances at the Cabaret Voltaire and using art to express their cloy with the war and the interests that inspired it. Having left Germany and Romania during World State of war I, the artists arrived in politically neutral Switzerland. They used abstraction to fight confronting the social, political, and cultural ideas of that time. They used stupor art, provocation, and "vaudevilleian excess" to subvert the conventions they believed had caused the Great State of war.[30] The Dadaists believed those ideas to exist a byproduct of bourgeois society that was so apathetic information technology would wage state of war confronting itself rather than challenge the status quo:[31]

We had lost confidence in our culture. Everything had to be demolished. We would begin again afterwards the tabula rasa. At the Cabaret Voltaire we began past shocking common sense, public opinion, education, institutions, museums, practiced taste, in short, the whole prevailing social club."

—Marcel Janco[32]

Ball said that Janco'due south mask and costume designs, inspired by Romanian folk fine art, fabricated "the horror of our time, the paralyzing groundwork of events" visible.[xxx] According to Ball, performances were accompanied past a "balalaika orchestra playing delightful folk-songs". Influenced by African music, arrhythmic drumming and jazz were common at Dada gatherings.[33] [34]

After the cabaret airtight down, Dada activities moved on to a new gallery, and Hugo Ball left for Bern. Tzara began a relentless campaign to spread Dada ideas. He bombarded French and Italian artists and writers with letters, and soon emerged as the Dada leader and master strategist. The Cabaret Voltaire re-opened, and is all the same in the same place at the Spiegelgasse i in the Niederdorf.

Zürich Dada, with Tzara at the helm, published the fine art and literature review Dada beginning in July 1917, with 5 editions from Zürich and the final 2 from Paris.

Other artists, such as André Breton and Philippe Soupault, created "literature groups to help extend the influence of Dada".[35]

After the fighting of the First Earth War had ended in the armistice of November 1918, nearly of the Zürich Dadaists returned to their home countries, and some began Dada activities in other cities. Others, such as the Swiss native Sophie Taeuber, would remain in Zürich into the 1920s.

Berlin [edit]

Comprehend of Anna Blume, Dichtungen, 1919

"Berlin was a city of tightened stomachers, of mounting, thundering hunger, where subconscious rage was transformed into a boundless money lust, and men's minds were concentrating more than and more on questions of naked existence... Fear was in everybody's basic" – Richard Hülsenbeck

Raoul Hausmann, who helped constitute Dada in Berlin, published his manifesto Synthethic Cino of Painting in 1918 where he attacked Expressionism and the art critics who promoted information technology. Dada is envisioned in dissimilarity to art forms, such as Expressionism, that appeal to viewers' emotional states: "the exploitation of so-called echoes of the soul". In Hausmann's conception of Dada, new techniques of creating art would open doors to explore new artistic impulses. Fragmented use of real world stimuli immune an expression of reality that was radically unlike from other forms of art:[36]

A child's discarded doll or a brightly colored rag are more necessary expressions than those of some donkey who seeks to immortalize himself in oils in finite parlors.

—Raoul Hausmann

The groups in Germany were not equally strongly anti-art as other groups. Their activity and art were more political and social, with corrosive manifestos and propaganda, satire, public demonstrations and overt political activities. The intensely political and state of war-torn environment of Berlin had a dramatic affect on the ideas of Berlin Dadaists. Conversely, New York'due south geographic distance from the war spawned its more theoretically-driven, less political nature.[37] Co-ordinate to Hans Richter, a Dadaist who was in Berlin yet "aloof from agile participation in Berlin Dada", several distinguishing characteristics of the Dada movement there included: "its political element and its technical discoveries in painting and literature"; "inexhaustible free energy"; "mental freedom which included the abolitionism of everything"; and "members intoxicated with their own power in a way that had no relation to the real world", who would "plough their rebelliousness fifty-fifty against each other".[38]

In February 1918, while the Neat State of war was approaching its climax, Huelsenbeck gave his first Dada oral communication in Berlin, and he produced a Dada manifesto afterward in the year. Post-obit the Oct Revolution in Russia, past then out of the war, Hannah Höch and George Grosz used Dada to express communist sympathies. Grosz, together with John Heartfield, Höch and Hausmann developed the technique of photomontage during this catamenia. Johannes Baader, the uninhibited Oberdada, was the "crowbar" of the Berlin movement'due south straight action according to Hans Richter and is credited with creating the first behemothic collages, according to Raoul Hausmann.

After the war, the artists published a series of short-lived political magazines and held the Kickoff International Dada Fair, 'the greatest project yet conceived by the Berlin Dadaists', in the summer of 1920.[39] Too equally work by the master members of Berlin Dada – Grosz, Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch, Johannes Baader, Huelsenbeck and Heartfield – the exhibition as well included the piece of work of Otto Dix, Francis Picabia, Jean Arp, Max Ernst, Rudolf Schlichter, Johannes Baargeld and others.[39] In all, over 200 works were exhibited, surrounded by incendiary slogans, some of which also ended upwards written on the walls of the Nazi'southward Entartete Kunst exhibition in 1937. Despite high ticket prices, the exhibition lost coin, with but i recorded auction.[40]

The Berlin group published periodicals such as Club Dada, Der Dada, Everyman His Own Football, and Dada Almanach. They likewise established a political party, the Fundamental Quango of Dada for the World Revolution.

Cologne [edit]

In Cologne, Ernst, Baargeld, and Arp launched a controversial Dada exhibition in 1920 which focused on nonsense and anti-bourgeois sentiments. Cologne's Early Bound Exhibition was fix in a pub, and required that participants walk past urinals while being read lewd verse past a adult female in a communion dress. The police closed the exhibition on grounds of obscenity, but it was re-opened when the charges were dropped.[41]

New York [edit]

Like Zürich, New York City was a refuge for writers and artists from the First Earth War. Before long later on arriving from France in 1915, Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia met American creative person Human Ray. Past 1916 the iii of them became the heart of radical anti-art activities in the The states. American Beatrice Wood, who had been studying in France, soon joined them, along with Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. Arthur Cravan, fleeing conscription in France, was also in New York for a time. Much of their activity centered in Alfred Stieglitz'southward gallery, 291, and the home of Walter and Louise Arensberg.

The New Yorkers, though not particularly organized, called their activities Dada, but they did not upshot manifestos. They issued challenges to art and civilisation through publications such as The Blind Man, Rongwrong, and New York Dada in which they criticized the traditionalist basis for museum art. New York Dada lacked the disillusionment of European Dada and was instead driven by a sense of irony and sense of humour. In his book Adventures in the arts: informal capacity on painters, vaudeville and poets Marsden Hartley included an essay on "The Importance of Being 'Dada' ".

During this fourth dimension Duchamp began exhibiting "readymades" (everyday objects found or purchased and declared art) such as a canteen rack, and was active in the Society of Independent Artists. In 1917 he submitted the now famous Fountain, a urinal signed R. Mutt, to the Society of Independent Artists exhibition but they rejected the slice. First an object of scorn within the arts community, the Fountain has since go almost canonized by some[42] every bit one of the near recognizable modernist works of sculpture. Art globe experts polled by the sponsors of the 2004 Turner Prize, Gordon'southward gin, voted it "the virtually influential work of modern art".[42] [43] As recent scholarship documents, the work is nonetheless controversial. Duchamp indicated in a 1917 letter to his sister that a female friend was centrally involved in the conception of this piece of work: "1 of my female friends who had adopted the pseudonym Richard Mutt sent me a porcelain urinal as a sculpture."[44] The piece is in line with the scatological aesthetics of Duchamp's neighbour, the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.[45] In an try to "pay homage to the spirit of Dada" a performance artist named Pierre Pinoncelli made a fissure in a replica of The Fountain with a hammer in January 2006; he also urinated on it in 1993.

Picabia's travels tied New York, Zürich and Paris groups together during the Dadaist menstruum. For vii years he also published the Dada periodical 391 in Barcelona, New York City, Zürich, and Paris from 1917 through 1924.

Past 1921, most of the original players moved to Paris where Dada had experienced its last major incarnation.

Paris [edit]

Man Ray, c. 1921–22, Rencontre dans la porte tournante, published on the cover of Der Sturm, Volume 13, Number 3, 5 March 1922

Human Ray, c. 1921–22, Dessin (Drawing), published on folio 43 of Der Sturm, Volume 13, Number 3, 5 March 1922

The French avant-garde kept abreast of Dada activities in Zürich with regular communications from Tristan Tzara (whose pseudonym means "sad in country," a name chosen to protest the treatment of Jews in his native Romania), who exchanged letters, poems, and magazines with Guillaume Apollinaire, André Breton, Max Jacob, Clément Pansaers, and other French writers, critics and artists.

Paris had arguably been the classical music capital of the world since the advent of musical Impressionism in the belatedly 19th century. One of its practitioners, Erik Satie, collaborated with Picasso and Cocteau in a mad, scandalous ballet called Parade. Get-go performed past the Ballets Russes in 1917, information technology succeeded in creating a scandal merely in a dissimilar style than Stravinsky'due south Le Sacre du printemps had washed almost v years earlier. This was a ballet that was clearly parodying itself, something traditional ballet patrons would manifestly have serious issues with.

Dada in Paris surged in 1920 when many of the originators converged there. Inspired by Tzara, Paris Dada presently issued manifestos, organized demonstrations, staged performances and produced a number of journals (the final 2 editions of Dada, Le Cannibale, and Littérature featured Dada in several editions.)[46]

The commencement introduction of Dada artwork to the Parisian public was at the Salon des Indépendants in 1921. Jean Crotti exhibited works associated with Dada including a work entitled, Explicatif begetting the word Tabu. In the same year Tzara staged his Dadaist play The Gas Heart to howls of derision from the audience. When information technology was re-staged in 1923 in a more professional production, the play provoked a theatre riot (initiated by André Breton) that heralded the separate within the motility that was to produce Surrealism. Tzara's last effort at a Dadaist drama was his "ironic tragedy" Handkerchief of Clouds in 1924.

Netherlands [edit]

In the Netherlands the Dada movement centered mainly around Theo van Doesburg, all-time known for establishing the De Stijl move and magazine of the same name. Van Doesburg mainly focused on poetry, and included poems from many well-known Dada writers in De Stijl such as Hugo Brawl, Hans Arp and Kurt Schwitters. Van Doesburg and Thijs Rinsema (a cordwainer and creative person in Drachten) became friends of Schwitters, and together they organized the and so-called Dutch Dada campaign in 1923, where van Doesburg promoted a leaflet nearly Dada (entitled What is Dada?), Schwitters read his poems, Vilmos Huszár demonstrated a mechanical dancing doll and Nelly van Doesburg (Theo'due south wife), played avant-garde compositions on pianoforte.

A Bonset sound-verse form, "Passing troop", 1916

Van Doesburg wrote Dada verse himself in De Stijl, although nether a pseudonym, I.K. Bonset, which was merely revealed after his expiry in 1931. 'Together' with I.Yard. Bonset, he also published a brusque-lived Dutch Dada magazine chosen Mécano (1922–three). Another Dutchman identified by K. Schippers in his written report of the movement in the Netherlands[47] was the Groningen typographer H. Northward. Werkman, who was in touch with van Doesburg and Schwitters while editing his ain magazine, The Next Call (1923–six). 2 more artists mentioned by Schippers were German language-born and eventually settled in the Netherlands. These were Otto van Rees, who had taken office in the liminal exhibitions at the Café Voltaire in Zürich, and Paul Citroen.

Georgia [edit]

Though Dada itself was unknown in Georgia until at least 1920, from 1917 until 1921 a group of poets called themselves "41st Degree" (referring both to the latitude of Tbilisi, Georgia and to the Celsius temperature of a loftier fever [equal to 105.viii Fahrenheit]) organized forth Dadaist lines. The most important figure in this group was Iliazd (Ilia Zdanevich), whose radical typographical designs visually echo the publications of the Dadaists. Subsequently his flight to Paris in 1921, he collaborated with Dadaists on publications and events. For example, when Tristan Tzara was banned from holding seminars in Théâtre Michel in 1923, Iliazd booked the venue on his behalf for the performance, "The Disguised Heart Soirée", and designed the flyer.[48]

Yugoslavia [edit]

In Yugoslavia, alongside the new art movement Zenitism, at that place was meaning Dada activeness between 1920 and 1922, run mainly by Dragan Aleksić and including work by Mihailo S. Petrov, Ljubomir Micić and Branko Ve Poljanski.[49] Aleksić used the term "Yougo-Dada" and is known to have been in contact with Raoul Hausmann, Kurt Schwitters, and Tristan Tzara.[50] [51]

Italy [edit]

The Dada movement in Italy, based in Mantua, was met with distaste and failed to brand a pregnant bear on in the world of fine art. It published a magazine for a curt time and held an exhibition in Rome, featuring paintings, quotations from Tristan Tzara, and original epigrams such as "True Dada is against Dada". One member of this group was Julius Evola, who went on to go an eminent scholar of occultism, every bit well equally a correct-fly philosopher.[52]

Japan [edit]

A prominent Dada grouping in Japan was Mavo, founded in July 1923 by Tomoyoshi Murayama, and Yanase Masamu later joined by Tatsuo Okada. Other prominent artists were Jun Tsuji, Eisuke Yoshiyuki, Shinkichi Takahashi and Katué Kitasono.

Dada, an iconic character from the Ultra Series. His design draws inspiration from the art movement.

In Tsuburaya Productions's Ultra Series, an conflicting named Dada was inspired past the Dadaism motility, with said grapheme get-go appearing in episode 28 of the 1966 tokusatsu serial, Ultraman, its design past character artist Toru Narita. Dada's design is primarily monochromatic, and features numerous sharp lines and alternate blackness and white stripes, in reference to the motion and, in item, to chessboard and Become patterns. On May xix, 2016, in celebration to the 100 yr ceremony of Dadaism in Tokyo, the Ultra Monster was invited to come across the Swiss Ambassador Urs Bucher.[53] [54]

Butoh, the Japanese dance-form originating in 1959, can exist considered to have direct connections to the spirit of the Dada movement, as Tatsumi Hijikata, one of Butoh'due south founders, "was influenced early on in his career by Dadaism".[55]

Russia [edit]

Dada in itself was relatively unknown in Russian federation, nonetheless, advanced fine art was widespread due to the Bolshevik's revolutionary calendar. The Nichevoki, a literary group sharing Dadaist ideals[56] achieved infamy after i of its members suggested that Vladimir Mayakovsky should go to the "Pampushka" (Pameatnik Pushkina – Pushkin monument) on the "Tverbul" (Tverskoy Boulevard) to clean the shoes of anyone who desired it, subsequently Mayakovsky declared that he was going to cleanse Russian literature.[56] For more information on Dadaism's influence upon Russian advanced fine art, see the book Russian Dada 1914–1924.[57]

Women of Dada [edit]

Often overlooked when discussing the history and foundations of Dada, it is necessary to shed light on the female artists who created and inspired art and artists akin. These women were often times in platonic or romantic relationships with the male Dadaists mentioned in a higher place simply are rarely written past the relative ties. However, each artist fabricated vital contributions to the motility. Other notable mentions that do not include the artists below are: Suzanne Duchamp, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Emmy Hennings, Beatrice Forest, Clara Tice, and Ella Bergmann-Michel.

Hannah Höch [edit]

Hannah Höch of Berlin is considered to be the merely female Dadaist in Berlin at the fourth dimension of the movement.[58] During this time, she was in a relationship with Raoul Hausmann who as well was a Dada artist. She channeled the aforementioned anti-war and anti-government (Weimar Republic) in her works just brought out a feminist lens on the themes. With her works primarily of collage and photomontage, she often used precise placement or detailed titles to callout the misogynistic ways she and other women were treated.[59]

Sophie Taeuber-Arp [edit]

Sophie Taeuber-Arp was a Swiss artist, instructor, and dancer who produced various types of art and handicraft pieces. While married to Dadaist Jean Arp, Taeuber-Arp was known in the Dada community for her performative dancing. As such, she worked with choreographer Rudolf von Laban and was written by Tristan Tarza for her dancing skills.

Mina Loy [edit]

London-built-in Mina Loy was known for existence active in the literary sector of the New York Dada scene. She spent time writing poetry, creating Dada magazines, and acting and writing in plays. She contributed writing to Dada journal The Bullheaded Homo and Marchel Duchamp's Rongwrong.

Poesy [edit]

Dadaglobe solicitation form letter signed past Francis Picabia, Tristan Tzara, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, and Walter Serner, c. week of Nov 8, 1920. This instance was sent from Paris to Alfred Vagts in Munich.

Dadists used shock, nihilism, negativity, paradox, randomness, subconscious forces and antinomianism to subvert established traditions in the aftermath of the Smashing War. Tzara'due south 1920 manifesto proposed cutting words from a newspaper and randomly selecting fragments to write poetry, a process in which the synchronous universe itself becomes an agile amanuensis in creating the art. A poem written using this technique would be a "fruit" of the words that were clipped from the commodity.[lx]

In literary arts Dadaists focused on poetry, particularly the and so-chosen sound poesy invented past Hugo Ball. Dadaist poems attacked traditional conceptions of verse, including structure, order, as well every bit the interplay of sound and the meaning of linguistic communication. For Dadaists, the existing system by which information is articulated robs language of its dignity. The dismantling of language and poetic conventions are Dadaist attempts to restore language to its purest and near innocent form: "With these audio poem, nosotros wanted to dispense with a linguistic communication which journalism had made desolate and impossible."[61]

Simultaneous poems (or poèmes simultanés) were recited by a group of speakers who, collectively, produced a chaotic and confusing set of voices. These poems are considered manifestations of modernity including advertising, engineering, and conflict. Unlike movements such equally Expressionism, Dadaism did not have a negative view of modernity and the urban life. The chaotic urban and futuristic world is considered natural terrain that opens up new ideas for life and fine art.[62]

Music [edit]

Dada was not confined to the visual and literary arts; its influence reached into audio and music. These movements exerted a pervasive influence on 20th-century music, peculiarly on mid-century avant-garde composers based in New York—among them Edgard Varèse, Stefan Wolpe, John Cage, and Morton Feldman.[63] Kurt Schwitters adult what he called sound poems, while Francis Picabia and Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes composed Dada music performed at the Festival Dada in Paris on 26 May 1920.[64] Other composers such as Erwin Schulhoff, Hans Heusser and Alberto Savinio all wrote Dada music,[65] while members of Les Half-dozen collaborated with members of the Dada movement and had their works performed at Dada gatherings. Erik Satie also dabbled with Dadaist ideas during his career, although he is primarily associated with musical Impressionism.[64]

Legacy [edit]

While broadly based, the movement was unstable. By 1924 in Paris, Dada was melding into Surrealism, and artists had gone on to other ideas and movements, including Surrealism, social realism and other forms of modernism. Some theorists contend that Dada was actually the start of postmodern art.[66]

By the dawn of the Second World War, many of the European Dadaists had emigrated to the United States. Some (Otto Freundlich, Walter Serner) died in expiry camps nether Adolf Hitler, who actively persecuted the kind of "degenerate art" that he considered Dada to represent. The movement became less active as post-war optimism led to the development of new movements in art and literature.

Dada is a named influence and reference of various anti-art and political and cultural movements, including the Situationist International and civilization jamming groups like the Cacophony Society. Upon breaking up in July 2012, anarchist popular band Chumbawamba issued a argument which compared their own legacy with that of the Dada fine art movement.[67]

At the same time that the Zürich Dadaists were making noise and spectacle at the Cabaret Voltaire, Lenin was planning his revolutionary plans for Russia in a nearby apartment. Tom Stoppard used this coincidence every bit a premise for his play Travesties (1974), which includes Tzara, Lenin, and James Joyce equally characters. French writer Dominique Noguez imagined Lenin equally a member of the Dada group in his tongue-in-cheek Lénine Dada (1989).

The former building of the Cabaret Voltaire fell into disrepair until it was occupied from Jan to March 2002, by a group proclaiming themselves Neo-Dadaists, led by Marking Divo.[68] The group included Jan Thieler, Ingo Giezendanner, Aiana Calugar, Lennie Lee, and Dan Jones. After their eviction, the space was turned into a museum dedicated to the history of Dada. The piece of work of Lee and Jones remained on the walls of the new museum.

Several notable retrospectives have examined the influence of Dada upon art and social club. In 1967, a big Dada retrospective was held in Paris. In 2006, the Museum of Mod Art in New York Metropolis mounted a Dada exhibition in partnership with the National Gallery of Fine art in Washington D.C. and the Middle Pompidou in Paris. The LTM label has released a large number of Dada-related sound recordings, including interviews with artists such every bit Tzara, Picabia, Schwitters, Arp, and Huelsenbeck, and musical repertoire including Satie, Ribemont-Dessaignes, Picabia, and Nelly van Doesburg.[69]

Musician Frank Zappa was a self-proclaimed Dadaist after learning of the movement:

In the early days, I didn't fifty-fifty know what to call the stuff my life was made of. You can imagine my delight when I discovered that someone in a distant land had the aforementioned idea—AND a squeamish, brusque name for it.[seventy]

David Bowie adjusted William S. Burrough's cut-up technique for writing lyrics and Kurt Cobain likewise admittedly used this method for many of his Nirvana lyrics, including "In Bloom".[71]

Art techniques developed [edit]

Dadaism besides blurred the line between literary and visual arts:

Dada is the background to abstract fine art and sound poetry, a starting indicate for performance art, a prelude to postmodernism, an influence on pop art, a celebration of antiart to be later embraced for anarcho-political uses in the 1960s and the movement that laid the foundation for Surrealism.[72]

Collage [edit]

The Dadaists imitated the techniques adult during the cubist move through the pasting of cut pieces of paper items, just extended their art to cover items such every bit transportation tickets, maps, plastic wrappers, etc. to portray aspects of life, rather than representing objects viewed as still life. They too invented the "risk collage" technique, involving dropping torn scraps of paper onto a larger sheet then pasting the pieces wherever they landed.

Cut-up technique [edit]

Cut-upwardly technique is an extension of collage to words themselves, Tristan Tzara describes this in the Dada Manifesto:[73]

TO MAKE A DADAIST Poem

Take a newspaper.

Accept some pair of scissors.

Choose from this paper an article of the length yous want to make your poem.

Cut out the article.

Next advisedly cut out each of the words that makes up this commodity and put them all in a purse.

Milkshake gently.

Side by side take out each cut ane after the other.

Copy conscientiously in the order in which they left the bag.

The verse form will resemble you.

And there y'all are – an infinitely original author of mannerly sensibility, even though unappreciated past the vulgar herd.

Photomontage [edit]

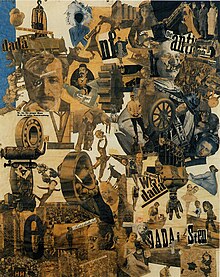

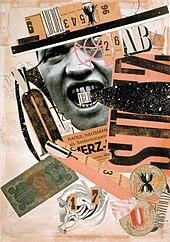

Raoul Hausmann, ABCD (cocky-portrait), a photomontage from 1923–24

The Dadaists – the "monteurs" (mechanics) – used scissors and glue rather than paintbrushes and paints to express their views of modern life through images presented by the media. A variation on the collage technique, photomontage utilized actual or reproductions of real photographs printed in the press. In Cologne, Max Ernst used images from the First Earth State of war to illustrate letters of the devastation of war.[74] Although the Berlin photomontages were assembled, like engines, the (non)relationships among the disparate elements were more than rhetorical than real.[75]

Assemblage [edit]

The assemblages were three-dimensional variations of the collage – the assembly of everyday objects to produce meaningful or meaningless (relative to the war) pieces of work including war objects and trash. Objects were nailed, screwed or fastened together in different fashions. Assemblages could be seen in the round or could be hung on a wall.[76]

Readymades [edit]

Marcel Duchamp began to view the manufactured objects of his collection as objects of fine art, which he called "readymades". He would add signatures and titles to some, converting them into artwork that he called "readymade aided" or "rectified readymades". Duchamp wrote: "One of import characteristic was the short sentence which I occasionally inscribed on the 'readymade.' That judgement, instead of describing the object like a championship, was meant to carry the mind of the spectator towards other regions more verbal. Sometimes I would add a graphic detail of presentation which in order to satisfy my peckish for alliterations, would exist called 'readymade aided.'"[77] One such example of Duchamp'southward readymade works is the urinal that was turned onto its back, signed "R. Mutt", titled Fountain, and submitted to the Society of Contained Artists exhibition that year, though it was not displayed.

Many young artists in America embraced the theories and ideas espoused past Duchamp. Robert Rauschenberg in item was very influenced by Dadaism and tended to utilise found objects in his collages equally a ways of dissolving the boundary between high and low civilisation.[78]

Artists [edit]

- Dragan Aleksić (1901–1958), Yugoslavia

- Louis Aragon (1897–1982), France

- Jean Arp (1886–1966), Germany, France

- Sophie Taeuber-Arp (1889–1943) Switzerland, France

- Johannes Baader (1875–1955) Germany

- Hugo Ball (1886–1927), Germany, Switzerland

- André Breton (1896–1966), France

- John Covert (painter) (1882–1960), Usa

- Jean Crotti (1878–1958), France

- Otto Dix (1891–1969), Germany

- Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931) Netherlands

- Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), French republic

- Suzanne Duchamp (1889–1963), France

- Paul Éluard (1895–1952), France

- Max Ernst (1891–1976), Frg, US

- Julius Evola (1898–1974), Italian republic

- George Grosz (1893–1959), Germany, France, Usa

- Raoul Hausmann (1886–1971), Germany

- John Heartfield (1891–1968), Deutschland, USSR, Czechoslovakia, UK

- Hannah Höch (1889–1978), Germany

- Richard Huelsenbeck (1892–1974), Federal republic of germany

- Georges Hugnet (1906–1974), France

- Marcel Janco (1895–1984), Romania, Israel

- Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874–1927), Frg, US

- Clément Pansaers (1885–1922), Kingdom of belgium

- Francis Picabia (1879–1953), French republic

- Homo Ray (1890–1976), France, US

- Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes (1884–1974), France

- Hans Richter, Germany, Switzerland

- Juliette Roche Gleizes (1884–1980), France

- Kurt Schwitters (1887–1948), Frg

- Walter Serner (1889–1942), Republic of austria

- Philippe Soupault (1897–1990), France

- Tristan Tzara (1896–1963), Romania, French republic

- Beatrice Wood (1893–1998), Us

See likewise [edit]

- Art intervention

- Dadaglobe

- List of Dadaists

- Épater la suburbia

- Happening

- Incoherents

- Transgressive art

References [edit]

- ^ World War I and Dada Archived 2017-12-01 at the Wayback Machine, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

- ^ Francis M. Naumann, New York Dada, 1915–23 Archived 2018-10-28 at the Wayback Automobile, Abrams, 1994, ISBN 0-81093676-3

- ^ Mario de Micheli (2006). Las vanguardias artísticas del siglo XX. Alianza Forma. pp. 135–37.

- ^ Trachtman, Paul. "A Brief History of Dada". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved xiv January 2017.

- ^ a b c Schneede, Uwe M. (1979), George Grosz, His life and piece of work, New York: Universe Books

- ^ a b c Budd, Dona, The Language of Art Knowledge, Pomegranate Communications.

- ^ Richard Huelsenbeck, En avant Dada: Eine Geschichte des Dadaismus, Paul Steegemann Verlag, Hannover, 1920, Erste Ausgabe (Die Silbergäule): English translation in Motherwell 1951, p.[ page needed ]

- ^ "Dada, Tate". Archived from the original on 2014-ten-26. Retrieved 2014-x-26 .

- ^ Timothy Stroud, Emanuela Di Lallo, 'Fine art of the Twentieth Century: 1900–1919, the advanced movements', Book ane of Fine art of the Twentieth Century, Skyra, 2006, ISBN 887624604-5

- ^ Middleton, J. C. (1962). "'Bolshevism in Art': Dada and Politics". Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 4 (3): 408–30. JSTOR 40753524.

- ^ Ian Chilvers; John Glaves-Smith, eds. (2009). "Dada". A Lexicon of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press. pp. 171–173. ISBN9780199239658. Archived from the original on 2021-03-02. Retrieved 2021-02-thirteen .

- ^ Dada Archived 2017-01-thirty at the Wayback Machine, The fine art history, retrieved March 13, 2017.

- ^ "Anti-art, Art that challenges the existing accepted definitions of art, Tate". Archived from the original on 2017-04-05. Retrieved 2014-x-26 .

- ^ a b "Dada", Dawn Adès and Matthew Gale, Grove Fine art Online, Oxford University Press, 2009 (subscription required) Archived 2018-03-12 at the Wayback Motorcar

- ^ Roselee Goldberg, Thomas & Hudson, L'univers de fifty'art, Chapter 4, Le surréalisme, Les représentations pré-Dada à Paris, ISBN 978-2-87811-380-eight

- ^ a b Richter, Hans (1965), Dada: Fine art and Anti-art, New York and Toronto: Oxford Academy Printing

- ^ Joan M. Marter, The Grove Encyclopedia of American Fine art, Volume 1, Oxford Academy Printing, 2011 Archived 2020-02-09 at the Wayback Auto, p. half dozen, ISBN 0195335791

- ^ Tzara, Tristan (1920). "Seven". La Vie des Lettres (in French). Paris.

- ^ DADA: Cities, National Gallery of Art, archived from the original on 2008-11-02, retrieved 2008-10-19

- ^ a b Fred South. Kleiner (2006), Gardner'due south Fine art Through the Ages (twelfth ed.), Wadsworth Publishing, p. 754

- ^ Hopkins, David, A Companion to Dada and Surrealism, Book 10 of Blackwell Companions to Fine art History, John Wiley & Sons, May two, 2016, p. 83, ISBN 1118476182

- ^ Elger 2004, p. half-dozen.

- ^ Motherwell 1951, p.[ page needed ].

- ^ "Tristan Tzara: Dada Manifesto 1918" Archived 2020-xi-30 at the Wayback Machine (text Archived 2021-04-14 at the Wayback Motorcar) by Charles Cramer and Kim Grant, Khan University

- ^ Wellek, René (1955). A History of Modern Criticism: French, Italian and Castilian criticism, 1900-1950 . Yale University Printing. p. 91. ISBN9780300054514.

Tzara second Dada manifesto,.

- ^ Novero, Cecilia (2010). Antidiets of the Avant-Garde. University of Minnesota Press. p. 62.

- ^ Elger 2004, p. 7.

- ^ Greeley, Anne. "Cabaret Voltaire". Routledge. Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Tom Sandqvist, Dada East: The Romanians of Cabaret Voltaire, London MIT Press, 2006.[ page needed ]

- ^ a b "Cabaret Voltaire: A Night Out at History'southward Wildest Nightclub". BBC. 2016. Archived from the original on 31 July 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "Introduction: "Everybody tin can Dada"". National Gallery of Art. Archived from the original on 2 November 2008. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- ^ Marcel Janco, "Dada at Two Speeds," trans. in Lucy R. Lippard, Dadas on Fine art (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1971), p. 36.

- ^ Jenkins, Ellen Jan (2011). Andrea, Alfred J. (ed.). World History Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO – via Credo Reference.

- ^ Rasula, Jed (2015). Destruction was My Beatrice: Dada and the Unmaking of the Twentieth Century. New York: Bones Books. pp. 145–146. ISBN9780465089963.

- ^ Europe of Cultures. "Tristan Tzara speaks of the Dada Movement" Archived 2015-07-04 at the Wayback Machine, September 6, 1963. Retrieved on July 2, 2015.

- ^ Elger 2004, p. 35.

- ^ Naumann, Francis Chiliad. (1994). New York Dada. New York: Abrams. ISBN0810936763.

- ^ Hans Richter, Dada: Fine art and Anti-Art, London: Thames & Hudson (1997); p. 122

- ^ a b Dada, Dickermann, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2006 p443

- ^ Dada, Dickermann, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 2006 p99

- ^ Schaefer, Robert A. (September seven, 2006), "Das Ist Dada–An Exhibition at the Museum of Modernistic Art in NYC", Double Exposure, archived from the original on October nine, 2007, retrieved June 12, 2007

- ^ a b Fountain' most influential piece of mod art Archived 2020-01-24 at the Wayback Machine, Independent, December 2, 2004

- ^ "Duchamp's urinal tops fine art survey" Archived 2020-05-09 at the Wayback Motorcar, BBC News December i, 2004.

- ^ Duchamp, Marcel, translated and quoted in Gammel 2002, p. 224

- ^ Gammel 2002, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Marc Dachy, Dada : La révolte de l'fine art , Paris, Gallimard / Centre Pompidou, drove "Découvertes Gallimard" (nº 476), 2005.

- ^ Schippers, Yard. (1974). Holland Dada. Amsterdam: Querido. [ pages needed ]

- ^ "Iliazd: From 41° to Dada". mcbcollection.com . Retrieved 2022-01-08 .

- ^ "Zenit: International Review of Arts and Culture". Archived from the original on 2017-09-01. Retrieved 2017-09-01 .

- ^ Dubravka Djurić, Miško Šuvaković. Impossible Histories: Historical Avant-gardes, Neo-avant-gardes, and Mail-avant-gardes in Yugoslavia, 1918–1991, p. 132 Archived 2020-02-26 at the Wayback Auto, MIT Press, 2003. ISBN 9780262042161; Jovanov Jasna, Kujundžić Dragan, "Yougo-Dada". "Crisis and the Arts: The History of Dada", Vol. Iv, The Eastern Orbit: Russia, Georgia, Ukraine, Central Europe and Japan, General Editor Stephen C. Foster, G.Thou. Hall & Comp. Publishers, New York 1998, 41–62

- ^ Jovanov 1999, p.[ page needed ].

- ^ "Julius Evola – International Dada Archive". Archived from the original on 2013-03-sixteen. Retrieved 2013-02-01 .

- ^ 「三面怪人 ダダ」が「ダダイズム100周年」を祝福!スイス大使館で開催された記者発表会に登場! (in Japanese). chiliad-78.jp. 2016-05-19. Archived from the original on 2016-06-23. Retrieved 2016-06-08 .

- ^ "Dada Celebrates Dadaism'south 100th Anniversary". tokusatsunetwork.com. 2016-05-19. Archived from the original on 2018-09-16. Retrieved 2016-06-08 .

- ^ Loke, Margarett (November 1987). "Butoh: Trip the light fantastic of Darkness". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2019-09-25. Retrieved 2019-09-25 .

- ^ a b Margarita Tupitsyn; Victor Tupitsyn; Olga Burenina-Petrova; Natasha Kurchanova (2018). Russian Dada: 1914-1924 (PDF). ISBN978-84-8026-573-seven. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ Russian Dada 1914–1924 by Margarita Tupitsyn (Editor), MIT Press: September 4, 2018]

- ^ "Here Are five Pioneering Women Of The Dada Art Movement". TheCollector. 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2022-01-08 .

- ^ "Here Are 5 Pioneering Women Of The Dada Art Movement". TheCollector. 2020-eleven-12. Retrieved 2022-01-08 .

- ^ Coutinho, Eduardo (2018). Brazilian Literature as Earth Literature. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 158. ISBN9781501323263.

- ^ Elger 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Morrison, Jeffrey; Krobb, Florian (1997). Text Into Image, Paradigm Into Text: Proceedings of the Interdisciplinary. Atlanta: Rodopi. p. 234. ISBN9042001526.

- ^ Greenbaumon, Matthew (2008-07-10). "From Revolutionary to Normative: A Secret History of Dada and Surrealism in American Music". NewMusicBox . Retrieved 2022-01-15 .

- ^ a b James Hayward. "Festival Paris Dada [LTMCD 2513] | Advanced Art | LTM". Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ Ingram, Paul (2017). "Songs, Anti-Symphonies and Sodomist Music: Dadaist Music in Zurich, Berlin and Paris". Dada/Surrealism. 21: 1–33. doi:10.17077/0084-9537.1334.

- ^ Locher, David (1999), "Unacknowledged Roots and Blatant Imitation: Postmodernism and the Dada Motility", Electronic Journal of Sociology, four (1), archived from the original on 2007-02-23, retrieved 2007-04-25

- ^ "Chumbawamba". Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ 2002 occupation past neo-Dadaists Archived 2008-12-01 at the Wayback Automobile Prague Mail service

- ^ "LTM Recordings". Archived from the original on 2012-01-14. Retrieved 2011-12-xx .

- ^ Frank Zappa, The Existent Frank Zappa Volume, p. 162

- ^ "How David Bowie, Kurt Cobain & Thom Yorke Write Songs With William Burroughs' Cut-Up Technique | Open Civilisation". Retrieved 2021-10-31 .

- ^ Marc Lowenthal, translator's introduction to Francis Picabia's I Am a Beautiful Monster: Verse, Prose, and Provocation

- ^ "manifestos: dada manifesto on feeble love and bitter honey by tristan tzara, 12th dec 1920". 391. 1920-12-12. Archived from the original on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2011-06-27 .

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain .

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain . - ^ "DADA – Techniques – photomontage". Nga.gov. Archived from the original on 2011-06-25. Retrieved 2011-06-11 .

- ^ Willette, Jeanne. "Dada and Photomontage | Art History Unstuffed". Retrieved 2022-01-15 .

- ^ "DADA – Techniques – assemblage". Nga.gov. Archived from the original on 2011-07-xvi. Retrieved 2011-06-11 .

- ^ "The Writings of Marcel Duchamp" ISBN 0-306-80341-0

- ^ "The Readymade - Development and Ideas". The Art Story . Retrieved 2022-01-15 .

Sources

- Elger, Dietmar (2004). Uta Grosenick (ed.). Dadaism. Taschen. ISBN 9783822829462.

- Gammel, Irene (2002). Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada and Everyday Modernity. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Jovanov, Jasna (1999). Demistifikacija apokrifa: Dadaizam na jugoslovenskim prostorima. Novi Sad: Apostrof.

- Motherwell, Robert (1951). The Dada Painters and Poets; an anthology. New York: Wittenborn, Schultz. OCLC 1906000.

Farther reading [edit]

- The Dada Almanac, ed Richard Huelsenbeck [1920], re-edited and translated by Malcolm Green et al., Atlas Press, with texts by Hans Arp, Johannes Baader, Hugo Ball, Paul Citröen, Paul Dermée, Daimonides, Max Goth, John Heartfield, Raoul Hausmann, Richard Huelsenbeck, Vincente Huidobro, Mario D'Arezzo, Adon Lacroix, Walter Mehring, Francis Picabia, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, Alexander Sesqui, Philippe Soupault, Tristan Tzara. ISBN 0-947757-62-seven

- Blago Hurl, Blago Bung, Hugo Brawl'due south Tenderenda, Richard Huelsenbeck'due south Fantastic Prayers, & Walter Serner's Last Loosening – 3 key texts of Zurich ur-Dada. Translated and introduced by Malcolm Green. Atlas Printing, ISBN 0-947757-86-4

- Ball, Hugo. Flight Out Of Time (University of California Press: Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1996)

- Bergius, Hanne Dada in Europa – Dokumente und Werke (co-ed. Eberhard Roters), in: Tendenzen der zwanziger Jahre. 15. Europäische Kunstausstellung, Catalogue, Vol.III, Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 1977. ISBN 978-3-496-01000-5

- Bergius, Hanne Das Lachen Dadas. Die Berliner Dadaisten und ihre Aktionen. Gießen: Anabas-Verlag 1989. ISBN 978-three-870-38141-7

- Bergius, Hanne Dada Triumphs! Dada Berlin, 1917–1923. Artistry of Polarities. Montages – Metamechanics – Manifestations. Translated by Brigitte Pichon. Vol. V. of the x editions of Crunch and the Arts: the History of Dada, ed. by Stephen Foster, New Haven, Connecticut, Thomson/Gale 2003. ISBN 978-0-816173-55-six.

- Jones, Dafydd Due west. Dada 1916 In Theory: Practices of Critical Resistance (Liverpool: Liverpool University Printing, 2014). ISBN 978-1-781-380-208

- Biro, Thousand. The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009. ISBN 0-8166-3620-half-dozen

- Dachy, Marc. Journal du mouvement Dada 1915–1923, Genève, Albert Skira, 1989 (Grand Prix du Livre d'Art, 1990)

- Dada & les dadaïsmes, Paris, Gallimard, Folio Essais, due north° 257, 1994.

- Dada : La révolte de l'fine art, Paris, Gallimard / Centre Pompidou, drove "Découvertes Gallimard" (nº 476), 2005.

- Athenaeum Dada / Chronique, Paris, Hazan, 2005.

- Dada, catalogue d'exposition, Centre Pompidou, 2005.

- Durozoi, Gérard. Dada et les arts rebelles, Paris, Hazan, Guide des Arts, 2005

- Hoffman, Irene. Documents of Dada and Surrealism: Dada and Surrealist Journals in the Mary Reynolds Collection, Ryerson and Burnham Libraries, The Art Institute of Chicago.

- Hopkins, David, A Companion to Dada and Surrealism, Volume 10 of Blackwell Companions to Fine art History, John Wiley & Sons, May 2, 2016, ISBN 1118476182

- Huelsenbeck, Richard. Memoirs of a Dada Drummer, (University of California Printing: Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1991)

- Jones, Dafydd. Dada Civilization (New York and Amsterdam: Rodopi Verlag, 2006)

- Lavin, Maud. Cut With the Kitchen Knife: The Weimar Photomontages of Hannah Höch. New Oasis: Yale University Press, 1993.

- Lemoine, Serge. Dada, Paris, Hazan, coll. Fifty'Essentiel.

- Lista, Giovanni. Dada libertin & libertaire, Paris, 50'insolite, 2005.

- Melzer, Annabelle. 1976. Dada and Surrealist Operation. PAJ Books ser. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1994. ISBN 0-8018-4845-viii.

- Novero, Cecilia. "Antidiets of the Avant-Garde: From Futurist Cooking to Consume Art." (University of Minnesota Printing, 2010)

- Richter, Hans. Dada: Art and Anti-Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 1965)

- Sanouillet, Michel. Dada à Paris, Paris, Jean-Jacques Pauvert, 1965, Flammarion, 1993, CNRS, 2005

- Sanouillet, Michel. Dada in Paris, Cambridge, Massachusetts, The MIT Press, 2009

- Schneede, Uwe M. George Grosz, His life and work (New York: Universe Books, 1979)

- Verdier, Aurélie. L'ABCdaire de Dada, Paris, Flammarion, 2005.

Filmography [edit]

- 1968: Frg-DADA: An Alphabet of German DADAism on YouTube, Documentary by Universal Pedagogy, Presented Past Kartes Video Communications, 56 Minutes

- 1971: DADA 'Archives du XXe siècle' on YouTube, Une émission produite par Jean José Marchand, réalisée par Philippe Collin et Hubert Knapp, Ce documentaire a été diffusé pour la première fois sur la RTF le 28.03.1971, 267 min.

- 2016: Das Prinzip Dada, Documentary past Marina Rumjanzewa, Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen (Sternstunde Kunst ), 52 Minutes (in German)

- 2016 Dada Art Movement History – "Dada on Tour" on YouTube, Bruno Art Group in collaboration with Cabaret Voltaire & Fine art Stage Singapore 2016, 27 minutes

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dada. |

| | Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dada |

- Dada Companion, bibliographies, chronology, artists' profiles, places, techniques, reception

- Dada at Curlie

- The International Dada Annal, University of Iowa, early Dada periodicals, online scans of publications

- Dadart, history, bibliography, documents, and news

- Dada audio recordings at LTM

- New York dada (magazine), Marcel Duchamp and Human being Ray, April, 1921, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Middle Pompidou (access online)

- Kunsthaus Zürich, 1 of the world's largest Dada collections

- "A Cursory History of Dada", Smithsonian Magazine

- Introduction to Dada, Khan University Art 1010

- National Gallery of Art 2006 Dada Exhibition

- Hathi Trust full-text Dadaism publications online

- Collection: "Dada and Neo-Dada" from the University of Michigan Museum of Art

Manifestos

- Text of Hugo Brawl'south 1916 Dada Manifesto

- Text of Tristan Tzara's 1918 Dada Manifesto

- Excerpts of Tristan Tzara'due south Dada Manifesto (1918) and Lecture on Dada (1922)

- Seven Dada Manifestos by Tristan Tzara

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dada

0 Response to "How Was the Dada Art Movement Described as Being Similar to New Media Activism"

Post a Comment